Migration of Humpbacks in the North Pacific Ocean

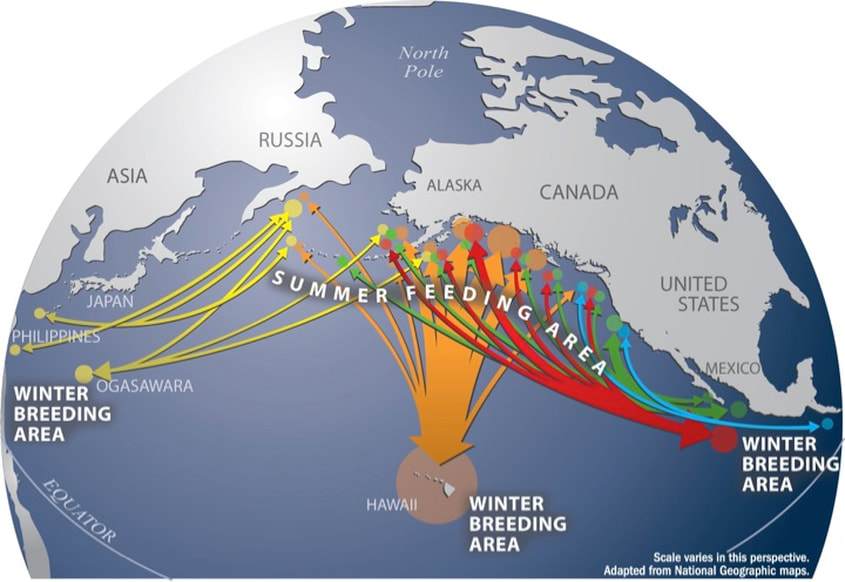

Humpbacks make long, trans-ocean migrations allowing them to spend summers in high latitudes feeding and winters in lower latitudes where the water is warmer and more conducive to birthing and breeding.

In the North Pacific Ocean, humpbacks can be found in waters of British Columbia, Alaska and eastern Russia foraging (feeding) during the summer season and in one of the major breeding areas in the winter months; Hawaii (most common), Central America, Mexico or Asia.

In the North Pacific Ocean, humpbacks can be found in waters of British Columbia, Alaska and eastern Russia foraging (feeding) during the summer season and in one of the major breeding areas in the winter months; Hawaii (most common), Central America, Mexico or Asia.

Image from: SPLASH study. Calambokidis et al. 2008

While humpbacks will follow this general seasonal pattern, there are exceptions and described migration patterns are really only general patterns observed. For example, humpbacks are expected to leave Alaska in winter months, though this is not always the case. Humpbacks can be observed in Alaskan waters every month of the year, though only in low numbers from December through March. Because there have been few documented cases of individual humpbacks in the foraging areas all year round, it is likely that the whales unexpectedly present in winter months are usually a combination of “late-departing” and “early-returning” migrating whales. Researchers have found strong breeding and feeding fidelity, or tendency for animals to return to the same areas year after year. This may be an indication that humpbacks are likely to feed and breed in the same areas as their mothers.

Interestingly, it is still unknown how humpbacks are capable of navigating to breeding and feeding grounds with such high success. It is quite intriguing that a whale in Juneau waters can weave its way out the channels and dead ends of the Inside Passage and make its way to the relatively small chain of Hawaiian Islands, located in the middle of the largest ocean basin on earth. While some theories exist, the exact methods used by humpbacks for navigation remain a mystery.

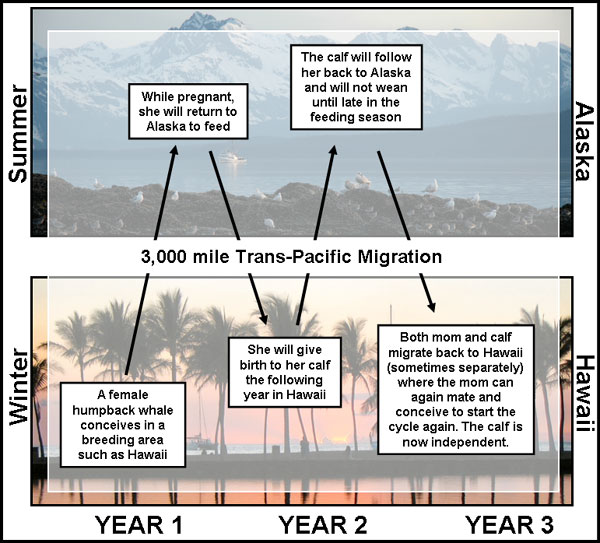

This migration takes humpbacks a minimum of about 30 days in each direction. The figure below follows the migration pattern of a female throughout a pregnancy and time with a dependent calf.

Interestingly, it is still unknown how humpbacks are capable of navigating to breeding and feeding grounds with such high success. It is quite intriguing that a whale in Juneau waters can weave its way out the channels and dead ends of the Inside Passage and make its way to the relatively small chain of Hawaiian Islands, located in the middle of the largest ocean basin on earth. While some theories exist, the exact methods used by humpbacks for navigation remain a mystery.

This migration takes humpbacks a minimum of about 30 days in each direction. The figure below follows the migration pattern of a female throughout a pregnancy and time with a dependent calf.

When humpback whales are migrating and in the breeding grounds, there is little to no available food. This is a time when humpbacks survive by metabolizing the food energy in their blubber stores. It is common for whales to return to Alaska from this migration having lost 1/3 of their body weight.

This time is especially taxing on new mothers. A female must nurse her calf immediately, though she herself is fasting. It is estimated that she delivers over 100 gallons of thick, 55% fat milk to her calf every day. Despite this obvious challenge, she will provide food for her calf for a number of months before she can get back to the feeding areas to replenish her blubber stores.

Underwater nursing poses unique challenges, which are overcome in a number of ways. First, nursing occurs in short bursts. Second, the mammary gland is triggered by direct pressure, so the calf can insert a rolled tongue into the mammary gland and trigger the flow of milk. Third, the consistency of the milk is thick, and much closer to what we would call yogurt, this helps the milk stay together rather than dispersing into the surrounding water.

This time is especially taxing on new mothers. A female must nurse her calf immediately, though she herself is fasting. It is estimated that she delivers over 100 gallons of thick, 55% fat milk to her calf every day. Despite this obvious challenge, she will provide food for her calf for a number of months before she can get back to the feeding areas to replenish her blubber stores.

Underwater nursing poses unique challenges, which are overcome in a number of ways. First, nursing occurs in short bursts. Second, the mammary gland is triggered by direct pressure, so the calf can insert a rolled tongue into the mammary gland and trigger the flow of milk. Third, the consistency of the milk is thick, and much closer to what we would call yogurt, this helps the milk stay together rather than dispersing into the surrounding water.